Rothbury Trees Blog

Read the latest blog articles about the trees in Rothbury and also information on trees species.

20 October 2025

How your 2025 Christmas Tree can help towards the purchase of the Rothbury Estate!

Choose your own tree, dig it up for planting in a pot, or have it cut. Either way, your donation will go directly to the Wildlife Trust Fund to purchase the Rothbury Estate.

Read More

2 October 2025

October Tree of the Month: Oak

Our extraordinary national tree.

Read More

3 September 2025

Season of Celebration!

So much good news heading our way!

Read More

1 September 2025

September Tree of the Month: Apple - and ORCHARDS!

We are on the cusp - summer is slipping away - autumn is calling, we can almost smell the change in the air.

Read More

3 August 2025

August Tree of the Month: Crab Apple

Along with Hawthorn, Blackthorn, and Wild Pear Trees, Crab Apples belong to the Rosaceae Family. They are one of our most wonderful native trees.

Read More

25 July 2025

What became of the fallen tree near the First School?

How Alan Winlow turned a fallen tree into an amazing material.

Read More

6 July 2025

July Tree of the Month: Sycamore

Hated by many, derided as a 'weed', this blog is in defence of the super Sycamore!

Read More

20 June 2025

Looking after our Standing People, young and old.

It is great that so many trees are being planted all over the place. But we need to properly look after the ones we already have. And we need to dedicate time to look after all the newly planted ones, also.

Read More

31 May 2025

June Tree of the Month: Hazel - plus, Ancient Woodland between the Coquet and the Wansbeck.

Living Woods hosted Max Adams, who told us about the Gospatrick Estate, and took us on a search for ancient woodland.

Read More

1 May 2025

May Tree of the Month: William's Cleugh Pines - a very special Scots Pine

We have Scots Pine in and around Rothbury. And at Kielder, a handful of Williams Cleugh Pines.

Read More

18 April 2025

The Trees at Beggars Rigg - Happy Anniversary!

In March 2022 Rothbury Tree Wardens, with Northumberland County Council officers, and volunteers from the community, planted 150 saplings, and five standard trees.

Read More

1 April 2025

Rothbury Tree of the Month: April, Alder

The native Alder enjoys damp, watery, surroundings.

Read More

1 March 2025

Rothbury Tree of the Month, March: Ash

March's tree is the beautiful, but endangered, Ash.

Read More

1 February 2025

Rothbury Tree of the Month, February: Rowan

February's tree is the magical Rowan, or Mountain Ash.

Read More

14 January 2025

Rothbury Tree of the Month: January 2025. The Yew.

Specific trees of Rothbury will highlighted each month during 2025. For January, let me introduce you to the rather wonderful Common Yew, in All Saints Graveyard.

Read More

7 January 2025

Happy Habitat Piles - and welcome to more diverse life in 2025!

After being cocooned and doped up on chocolate for a few weeks, who is ready to begin the new year by helping to ensure a greater diversity of creatures in the garden this spring and summer?

Read More

8 December 2024

Help Hospice Care - buy a Christmas tree today!

Hurry, as there are only a very few left. Purchase by donation, your donation will be doubled by the Big Give! BUT..you need to buy before noon on Tuesday 10th December.

Read More

20 November 2024

Harvesting the Willow at Chester Hope, Northumberland.

Rothbury Tree Wardens helped with the Willow Harvest at Chester Hope. We learned a great deal about this stunning, and useful, crop.

Read More

4 November 2024

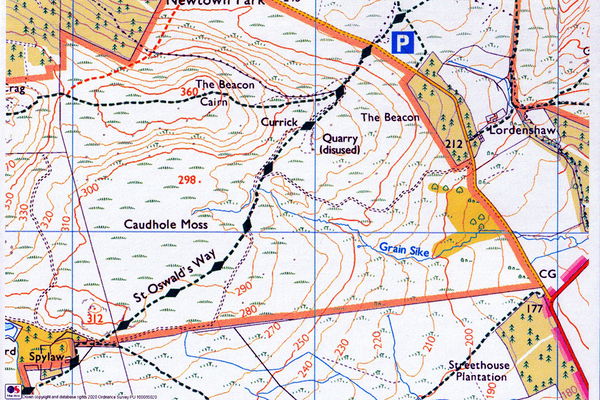

Getting Bogged Down in Bogs!

I was telling my good friend, Alan Winlow, about the bogs we saw on our recent visit to Moss Peteral farm. Describing the feeling of mystery, and other-worldliness it provoked in me, I was enthusiastically recalling the thrill of threading down metre long poles, to find the bog there was about 5000 years old! ‘Come with me, to Caudhole Moss’ Alan replied. I will show you a local bog which is older, and which needs help, urgently’.

Read More

15 October 2024

Launch of the Belsay Tree Trail!

'Veteran Nick' (Nick Johnson from the Northumbria Veteran Tree Project) proudly showed us the newest Tree Trail from the Veteran Trees Tree Trail App.

Read More

2 October 2024

Hey! It's time to order your FREE TREE!

NCC's fantastic free tree giveaway is back for 2024 - with 15,000 saplings up for grabs!

Read More

24 September 2024

Crimes Against Trees in our Green Spaces

Frustration is growing at the careless way some management companies treat trees in public spaces. This summer, one tree died, thankfully hurting no-one as it fell, and one had to felled before it went the same way. It is unacceptable and it needs to stop. We should be protecting, not killing, trees.

Read More

16 September 2024

A new approach to ash dieback

This beautiful old ash has been suffering from ash dieback for several years. In the past, it would simply have been felled, as thousand before it have been.

Read More

13 August 2024

The Trees of Rothbury Village Greens

Mike Evens is Rothbury's gardener. He told me: There are 59 trees on Rothbury's village greens; this includes the latest planted trees which have been donated by The Over-60s club (a crab apple) and Rothbury WI I (a rowan) in 2024. RPC is also responsible for the care of the trees in the closed graveyards at Haw Hill and All Saints Church, and Whitton Bank Cemetery. Overall, there are more than 170 trees.

Read More

13 August 2024

Tree Warden Training and Events

Training for Rothbury Tree Wardens. We have guests and members who share their knowledge at different times throughout the year. This was the first training we put on; it was very enjoyable - we learned a lot.

Read More

4 August 2024

Introducing Alan Winlow, MBE, Freeman of Whitton and Tosson, Rothbury Tree Warden

Alan Winlow has been honoured at many levels for his achievements in industry, education, and the environment. One award, from the Lindbergh Foundation, says: ’The human future depends on our ability to combine the knowledge of science with the wisdom of wildness’. Alan’s life exemplifies this philosophy.

Read More

10 June 2024

Ouch! That looks sore! And.. Take care of the trees, please!

Northumberland County Council is committed to give away 150,000 trees between 2020 and 2030. That is the equivalent of one tree per Northumberland household. Unfortunately, England is way behind its target of planting 120 million trees by 2025*, even though a massive amount of trees has been planted in recent years. And... a great many of these newly planted trees have not survived.

Read More

29 March 2024

Tree Trail updated!

I am delighted to tell you that the popular Rothbury Tree Trail has been updated for 2024.

Read More

4 March 2024

The last of the Ash?

I wonder how long the ash trees will last - how many will survive the dieback which is decimating them throughout the country. Lots, I hope.

Read More

31 January 2024

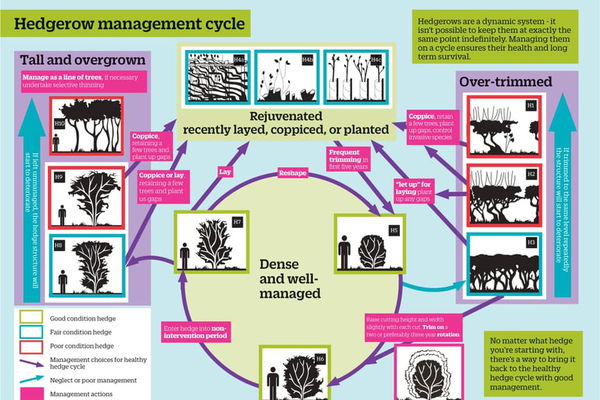

What makes a good hedge?

Hedges provide wildlife corridors, they help with water retention, and of course, they are excellent in helping livestock - browsing, but also both for shade in the summer, and shelter in the winter. But what makes a 'good' hedge?

Read More