What became of the fallen tree near the First School?

Friday, 25 July 2025

It was quite a shock, walking up the bank, and finding one of the old trees had broken in half, the large top half crashing into the road, and breaking through the garden wall. What a massive relief that no-one was hurt!

The wall was smashed and the trunk was half across the road, and half in the garden.

The fall was reported immediately, and Ian Longstaff set about sorting out the tree, removing it from the road.

I went to have a look at the remains, on the bank, to find any clues.

Remaining wood looked spongy and felt soft.

I am still unsure exactly what disease this tree has/had. But the remaining trunk seems resilient, thank goodness.

Alan Winlow had an idea about what to do with the fallen tree in the garden. And this blog is about what he did.

Here is the garden side, with the wood within the garden, after Ian has cleared the road.

Alan decided to conduct a trial with the twigs and small branches, turning them into biochar.

What is Biochar?

The RHS website tells us the following:

'Biochar' is a catch-all term describing any organic material that has been carbonised under high temperatures (300-1000°C), in the presence of little, or no oxygen. This process (called 'pyrolysis') releases bio-oils plus gases and leaves a solid residue of at least 80% elemental carbon which is termed biochar.

Virtually any organic material can be pyrolysed to make biochar. Different biochar feedstocks result in biochar with different properties, which is why it is important to know what material your biochar has been made from. Examples include soft plant tissue, woody materials, and manures. The property all of these biochars share is that they are carbon rich and don't readily decompose.

The idea of using biochar in soils was born from observing the man-made 'Terra Preta' soils of the Amazon. The fertility of the poor, acid soils in this region is thought to have been improved through addition of charred organic material by the area's indigenous inhabitants: helping to sustain population expansion across the Amazon region.

Biochar retains much of the open capillary structure from the original wood, including Xylem vessels. (These are the pipework in plant stems that transport water and minerals from the roots to the rest of the plant. xylem vessels.)

In soil these channels continue to function as conduits for air, water, nutrients and biology.

Alan cut up the wood, and his daughter Sarah and family tidied up the site, cutting and breaking the small diameter branches and twigs into lengths and putting them into bags for easy handling and transport.

After the twigs had dried, Alan set them on fire in a special kiln called a Kon Tiki kiln. The angled sides of this kiln control the combustion process by allowing oxygen only to the top layer, where the flame is burning.

The area below the flame is oxygen-starved but remains hot due to the flame above heating it like an oven.

The hot area is the pyrolysis zone, where biochar is created.

.

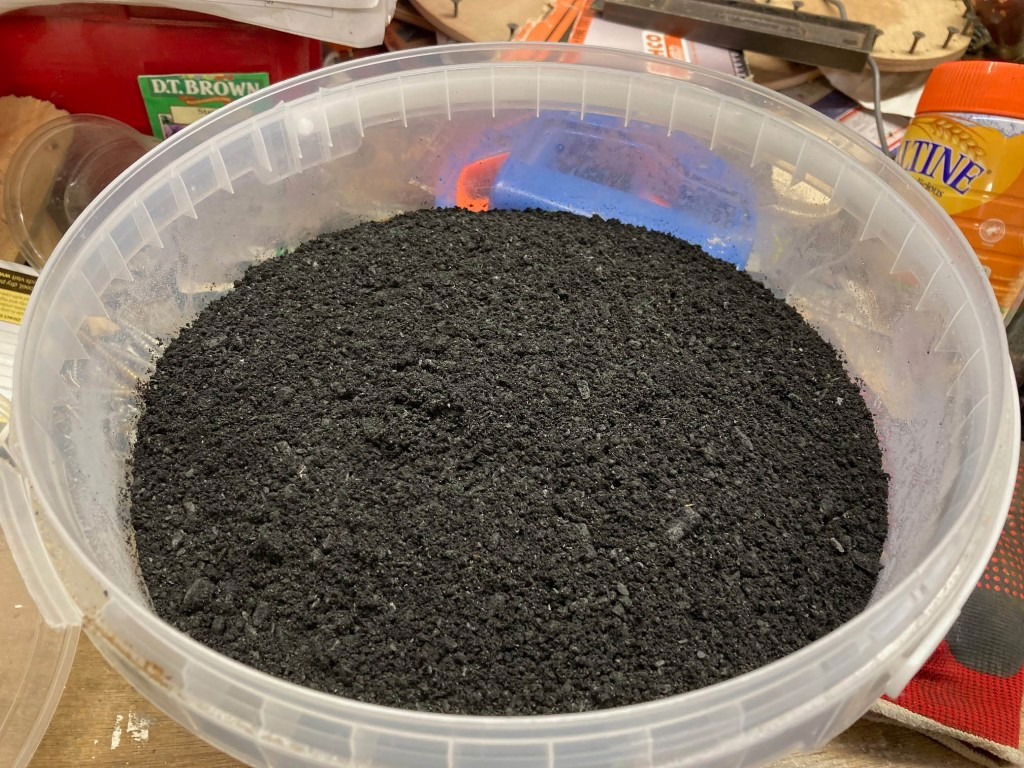

When the burning layer of twigs was four inches from the top, the fire was allowed to die down and then quenched with two watering cans of water, washing away a thin layer of ash, to reveal a large quantity of charred twigs - the biochar!

The biochar was crushed and passed through a 10mm sieve to produce the finished result. Wonderful!

The beautiful result!

This is how Alan explained it.

"Not long ago, a dead tree fell over the lane up to Rothbury First School, and a substantial amount of it landed in Sarah's garden.

I processed a trailer load of logs from the larger diameter branches, but what to do with the trailer load of twigs?

The solution was to conduct a trial burn to produce biochar using a small Kon Tiki kiln that Melvin at Newtown Engineering made for me a long time ago.

I have crushed a trial amount for use as a soil enhancer. Yet another way to lock up all this carbon!

It is a magical process"

I agree, and intend to find our much more about this special material.